Grief & Contemporary Grief Theories

What is Grief?

Grief is a reaction to the loss of someone or something to which an individual has a bond or connection. Loss affects everyone, neurotypical and autistic alike.

Some basic facts about grief:

- People experience a range of reactions to loss; the experience of grief is highly individualized.

- Grief can affect people in many ways, including cognitively, emotionally, physically, behaviorally, and spiritually.

- Some grief responses are more socially sanctioned and/or more noticeable than others, but all responses should be validated.

- Counter to popular belief, grief does not follow a timetable or “stages.” Some people may seem to process their grief quickly, while others take longer. Grief also can be triggered months or years after a loss.

- Grief can begin before a loss; for example, a long illness may involve grieving multiple losses as abilities and roles change.

- Adults grieve all kinds of losses, including non-death losses that may ultimately impact a person’s well-being. The end of a relationship through divorce or other circumstance is an example of a non-death loss.

- Losses may also include loss of the ability to participate in an activity, such as a job or enjoyable pastime. If an object of importance is lost, feelings of grief can also surround the absence of that object.

- Individuals have different styles of grieving. Some are highly emotive; others focus on a task such as a project or activity as a way of expressing grief. Others use both styles. Grieving styles can differ among families or friends. See Grieving Styles to learn more.

- Circumstances surrounding a death can impact the grief experience. A sudden, unexpected death can shatter a person’s previous sense of safety. Major life changes resulting from a death can also have a profound effect.

- No manner of grieving is “wrong” unless the griever’s behavior is harmful to themselves or others.

- People often cope with grief in the same ways in which they have coped with previous crises in their lives. Some grievers may benefit from support groups or peer support. Others may find comfort in reading books or websites about grief. Others may cope well on their own without formal support.

- There is no fixed timeline, but most people who are grieving return to levels of previous functioning around six months after a loss. While there is little research on grief in the autistic population, numerous interviews conducted in preparation for this website suggest that some adults with autism may exhibit only limited grief reactions until months or years after a loss. Again: there is no timeline for grief.

- In addition, an autistic person may exhibit emotions and reactions that are typically not recognized as grief by neurotypical people. If concerns arise about a griever who does not seem to be coping adequately and grief seems to persist, consider referral to a professional grief counselor. Visit Searching for Professional Help for suggestions.

Contemporary Grief Theories

Although research subjects have not traditionally included autistic adults, understanding current grief theory can be helpful to any professional working with any grieving individual. Perhaps most importantly, professionals should absolve themselves of the notion that grief occurs in stages. This theory was developed in the 1960s by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, a pioneer in the field of death and dying. She based her work exclusively on observations of people with terminal illness who were grieving the pending loss of their own lives. Stage theory has long been debunked as applicable to people who are dying and survivors who are grieving, but the notion persists among both professionals and laypeople. Stage theory can be unhelpful and even harmful to grievers, as they may conclude that they aren’t grieving “correctly” when their grief process does not follow a linear path—which, in fact, no one’s grief process does.

Significant contemporary grief theories are evidence-based and inform the support of those who are experiencing grief. While these theories are based on research conducted using neurotypical individuals, they illustrate some of the grief experiences and feelings of autistic adults, as well as issues that may complicate grief in persons on the autism spectrum.

Worden’s Tasks of Mourning Model

William Worden’s Task Model of Mourning describes the full grief journey as a series of tasks that must be accomplished to successfully process grief. These tasks are not ordered, prescriptive, or linear; they can be revisited and reworked throughout the grieving process (Worden, 1982).

- First Task: Accept the reality of the loss. Bereaved persons need to acknowledge the reality of the loss of the deceased.

- Second Task: Experience the pain of grief. Most people understand that losing a loved one is painful. Part of the grief journey involves experiencing this pain and, in fact, experiencing all the emotions of grief. Feelings like anger, guilt, and loneliness are all normal reactions to loss. Grievers may need to “dose” these emotions for themselves, and even back away from the pain at times, reapproaching it as they are able to handle it effectively.

- Third Task: Adjust to life without the deceased. Life without the person who died is irrevocably changed, and these changes require a griever to adjust to a new life without them. Different types of adjustments that a griever might face include:

-

- External adjustments (roles and functioning): This could mean learning new concrete skills such as mowing the lawn or balancing a checkbook. It may also include seemingly smaller adjustments, such as eating dinner or watching television without the deceased.

- Internal adjustments (sense of self or self-efficacy): The bereaved person may ask themselves questions such as “Who am I now without the person who died?”

- Spiritual adjustments (shattered assumptions, beliefs, or values): Losses often shatter the assumptive world of a griever, the idea that the world is essentially safe. Spiritual and religious beliefs may also be impacted, either by being strengthened or challenged with new questions or internal conflicts.

- Fourth Task: Finding an enduring connection while embarking on a new life. Bereaved people maintain continuing bonds with their loved ones after a death (Klass et al., 1996). This may include thinking about the deceased, participating in rituals of remembrance, or even wearing a favorite article of the deceased’s clothing. These tangible reminders of continuing bonds help the grieving person embark on a new life without the deceased but with less fear of losing the connection.

Continuing bonds are not helpful for everyone, and in some cases can be destructive or damaging. For example, if the relationship with the deceased was strained or unhealthy (e.g., enmeshed, co-dependent, or, at the extreme, abusive), maintaining bonds may continue unhealthy patterns of attachment. In other cases, the amount of effort the griever invests into continuing bonds may be all-consuming and lead to maladaptive behaviors that prevent the griever from participating in activities of daily living or from establishing healthy attachments to others in their life.

Task Theory and Autism

For a person on the spectrum, grief tasks can be impacted by autism itself. The emotional impact of the loss actually may be more intense than in the neurotypical population; however, to a professional without autism experience, that reality may not be apparent due to autistic communication styles and behaviors. This may be especially true with autistic adults who use devices or others who don’t use spoken language. Furthermore, if the death was that of their caregiver, the autistic person’s necessary adjustments may include life-altering changes. A primary caregiver’s death often leads to a cascade of losses beyond the death itself: the loss of a primary relationship, possibly the loss of a home, the related loss of a community, and subsequently the loss of stability and familiar routines. Routines and structure are often very important for those on the spectrum and disruptions can be profoundly distressing. The death of a primary caregiver might literally re-order their entire lives.

The grief experience is unique; therefore Worden’s tasks are mediated by the lived experience of each griever. Mediating factors include:

- Kinship: the griever’s familial relationship to the deceased (such as a spouse, child, or parent)

- Attachment: the nature of the relationship (including the strength of attachment, any unfinished business, and whether it was a conflicted relationship)

- Death factors: the cause of death; whether it was sudden or expected, preventable, or violent, all play a role in the grieving process of a loved one. A death following a long illness can still be experienced as a sudden death.

- Personal history: the griever’s experience with previous losses

- Personality variables: the griever’s coping style, attachment style, cognitive ability, mental health, and self-esteem

- Social factors: the level and quality of support available to the grieving person (including family resources, religious resources, community resources, etc.)

- Concurrent stresses: any secondary losses or other losses surrounding the death

Dual Process Model

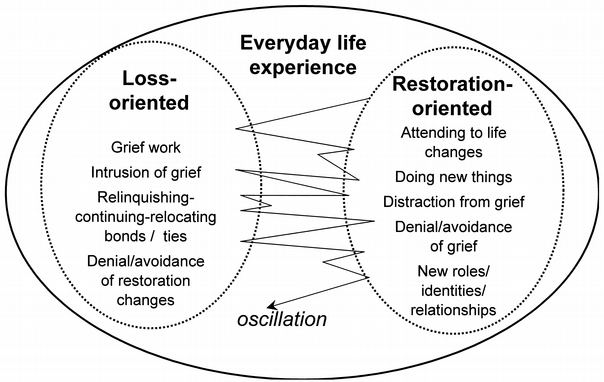

Researchers Dr. Margaret Stroebe and Dr. Henk Schut developed the Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement (2010). They propose that bereaved individuals oscillate between loss-oriented and restoration-oriented responses as they cope with loss.

Loss-oriented responses include:

- Grief work

- Intrusion of grief

- Letting go: continuing/relocating bonds

- Denial/avoidance of restoration changes (which are described below)

Restoration-oriented responses include:

- Attending to changes in life resulting from the loss

- Doing new things

- Distracting oneself from grief

- Denying/avoiding grief

- Investing in new roles, identities, or relationships

The oscillation between these two orientations allows the grieving individual to experience the emotions and other impacts of grief while also continuing through daily life. Therefore the tendency of autistic individuals to become highly focused on one thought or activity could inhibit their ability to oscillate. Oscillation should be encouraged to all grievers to prevent emotional overload. Overload of loss-oriented responses may lead to prolonged or complicated grief, and in restoration-oriented overload there may be inhibited grief reactions or stress disorders.

Since understanding and processing emotions is a common challenge in autism, these reactions may be compounded in autistic adults. Professionals should allow and encourage the bereaved individual to move between these two orientations, and to use this model to assure autistic people that this process is very common for grievers.

Conducting a Loss Inventory

Grief assessment often includes conducting a personal history of previous losses experienced by an individual. This “inventory” of prior events involving loss can help to identify ways that former losses are influencing a person’s grief. In addition, an inventory may reveal an individual’s coping behaviors, styles, and adaptations to prior loss, which can help guide the most useful responses, supports, and interventions.

Given the wide range of the autism spectrum, professionals should employ techniques that enable effective, individualized assessment (visit the section Autism & Grief for more information). Non-speaking individuals, for example, can be invited to respond to pictures or other visual prompts. If this is unsuccessful and there is no other option to communicate directly, clinicians may need to seek assistance from family members or others in the person’s network to conduct the inventory.

A loss inventory should gather the following types of information:

- Were there prior death losses and when did they occur?

- How did the individual respond to those prior losses? What type of support was helpful, and what was not?

- Are these previous losses affecting responses to the current loss?

- How are secondary losses that resulted from the previous loss affecting the individual? For example, did the prior death lead to any changes in the individual’s life, such as loss of other relationships, changes in daily routine, loss of treasured activities or objects, or a change in living situation?

- Have there been non-death losses and when did they occur? Non-death losses can include divorce; relocation; loss of relationships with parents, siblings, caregivers, partner, spouse, friends, or housemates; or loss of an object or cherished activity.

- Have there been pet/animal companion losses or separations? These losses are especially profound for many people on the spectrum.

- Based on these experiences, what type of support would be helpful with the current loss?

When taking this inventory:

- Account for inconsistent responses. Attempt to understand underlying factors if the individual’s way of coping with a current loss seems different from the ways they have coped in the past.

- Assess for trauma. A traumatic loss often influences grief responses. Has the person experienced any traumatic losses or changes, including bullying, ostracization, or rejection that now contribute to a loss of faith in other persons or in beliefs, or makes them feel more vulnerable?

Helpful Evidence-Based Terms That Can Be Used to Support and Understand Grief

Some terms which might be helpful for professionals supporting grievers, especially autistic grievers, are discussed below. Please note that this list is not exhaustive. Also, it is important to recognize that these are not diagnostic criteria; most often individuals will process their grief without professional intervention.

Anticipatory Grief

First described by psychiatrist Erich Lindemann (1944), anticipatory grief is the grief an individual may experience when they are aware of the impending death of a loved one. Anticipatory grief can be experienced by patients and their intimate network of family and friends, as well as professional caregivers. In more current research, Dr. Therese Rando (1988) expands the definition to include not only the mourning of an impending death, but also the many losses that may be experienced during an illness, such as the loss of functions, roles, and relationship. Persons with life threatening illness are not only mourning their impending death, but also the losses often experienced during the course of an illness, such as the loss of functions, roles, and relationships. Research indicates that anticipatory grief does not lessen or shorten the grief a survivor may experience after a loved one dies.

Chronic or Prolonged Grief

Chronic or prolonged grief describes grief which seems to remain at the same intensity level as the initial acute grief experience. Although experts disagree about how or when to define grief as being prolonged or chronic, most will agree that it is when the grief does not begin to ameliorate over time. Recently, the diagnosis of prolonged grief disorder was added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, known as the DSM-5. This controversial addition to the manual was recognition that, for a small minority of the bereaved, intense yearning for the deceased may persist for a year or more to the point of being debilitating.

Complicated Grief

Much like chronic or prolonged grief, there is significant disagreement about what constitutes grief that is complex or complicated. As with chronic or prolonged grief, the distinction is usually considered from a functional perspective. When the grief experience is so extreme that the person is unable to function, to build or maintain existing or new emotional attachments at a level that they did prior to the loss, and/or is experiencing symptoms indicative of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, or depression, this could be indicative of complex or complicated grief. Professional intervention may be required to help the griever re-establish healthy, adaptive behaviors and relationships.

Disenfranchised Grief

Dr. Kenneth Doka, an international expert on grief, developed this term (1989) to describe the experience of a person whose grief is not respected or supported by their community or within society at large. It The term also describes the grief experience of a person who has been regularly marginalized by society, and who thus receives less support or respect in their grief. Disenfranchised grief can and does occur for people with autism, even unintentionally. Some examples include when an autistic individual is prevented from participating in the funeral or other rituals, or when their expression of grief appears different from others in the family or community and therefore is not socially approved.

Intuitive or Instrumental Grief

These terms from the work of Dr. Kenneth Doka and Dr. Terry Martin (2010) are often used when describing someone’s grieving “style.” Individuals who use intuitive coping mechanisms find comfort in expressing their grief through language or sharing of emotions with others. Individuals who use instrumental expressions of grief may be more inclined to take action and find comfort in task-oriented coping mechanisms, such as making a music playlist for the funeral or raising funds in honor of the person who died. Most individuals use a combination of approaches, but many will demonstrate a preference for either emotion-oriented or task-oriented coping.

Meaning Making

Much like Worden’s Fourth Task of Mourning (see above), many researchers (including Dr. Robert Neimeyer) have posited that one aspect of processing or healing from grief is through finding ways to make meaning of the loss. Many people turn to their faith and/or other forms of spirituality, but meaning making can take many forms, such as advocating for others (i.e., Mothers Against Drunk Driving) or creating a memorial, such as a monument or a scholarship. Meaning making can also be more personal, such as dedicating a life choice or experience to the deceased.

References:

Klass, D., Silverman, P. R., & Nickman, S. L. (1996). Continuing bonds: New understandings of grief. Taylor & Francis.

Lindemann, E. (1944). The symptomatology and management of acute grief. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151 (6), 141-148.

Neimeyer, R. A. (Ed.). (2001). Meaning reconstruction & the experience of loss. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10397-000

Rando, T. A. (1988). Anticipatory Grief: The Term is a Misnomer but the Phenomenon Exists. Journal of Palliative Care, 4(1-2), 70-73. doi:10.1177/0825859788004001-223

Stroebe M, Schut H. The Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement: A Decade on. OMEGA – Journal of Death and Dying. 2010;61(4):273-289. doi:10.2190/OM.61.4.b

Worden, J. W. (1982). Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner. Springer.